Thanks to Suzanne, whose photos of western Victoria have intrigued me for a long time. When I showed interest in volcanos, she introduced me to the Kanawinka website, and thus this jaunt was born.

Where do I begin recounting our geological adventure? Ten days away were filled with so many half-grasped discoveries that my ignorance began to weigh heavily on me. My son cold-comforted me by saying “You should come back with more understanding than you left with.” That would not be hard, but neither is it enough. I'm reminded yet again that knowledge is the reward for hard work.

The Kanawinka Geotrail tracks volcanic activity from Portland in Victoria to Narracoorte in South Australia, an area internationally recognised as the Kanawinka Global Geopark. It includes more than sixty sites: craters, caves, plateaus, waterfalls, cones, lava flows, lakes, tumuli, mountains. “Kanawinka” is an Aboriginal word meaning the land of tomorrow: it encapsulates for me the nature of geology – geological activity in the distant past is in fact creating the land of tomorrow, and continues to do so.

The flat plains of western NSW

First thought is that the horizon-to-horizon flatness of western NSW offers nothing of geological interest. And then you discover that the vast flat plains were formed as equally vast mountains disintegrated. No landscape lacks a geological pedigree.

Gariwerd (The Grampians)

The Grampians aren't part of the volcano story, but of course they are part of the geological story, and their geology has created spectacular landscapes. From Hall's Gap to Dunkeld is about 60 kilometres and all the way you are driving beside or towards dramatic bluffs and cliffs. This is Carboniferous sandstone country: the sandy sediments formed 350 million when this was the eastern shoreline of Australia. An ancient beach became high mountain as the sediments were tilted and uplifted in the Middle Devonian Period to form a cuesta escarpment, long and gentle heavily wooded slopes to the west and precipitous cliffs and steep slopes facing east.

A gentle stroll from a car park took us to Silverband Falls, a narrow stripe of water falling vertically over horizontal rock banding: a recognisable sedimentary pattern, or am I being too simple-minded?

Nigretta Falls, well outside the Grampians, are a very different kettle of fish. They are formed of 410-million-year-old volcanic rock: complex crack patterns in the hard rock shape the form of the falls, producing a series of cascades which finally fall into a pool and then gurgle off in a chatty river.

Finally we get around to the real business of a volcanic area – rims and craters. We circumambulate four rims (the Blue Lake at Mt Gambier, Mt Schank, Mt Napier and Budj Bim previously known as Mt Eccles) and encounter three crater lakes, and two dry craters.

Mt Gambier

Mt Gambier is famous for its blue lake. We saw it first, an eye-searing blue in the late afternoon, but when we walked around it the next morning it was a subdued greyish blue. A couple of local women apologised because we weren't seeing their lake at its best. I have a very strong memory of walking around that lake 50-odd years ago, but it soon became obvious that this was impossible. My memory has been defective for a lot longer than I thought!

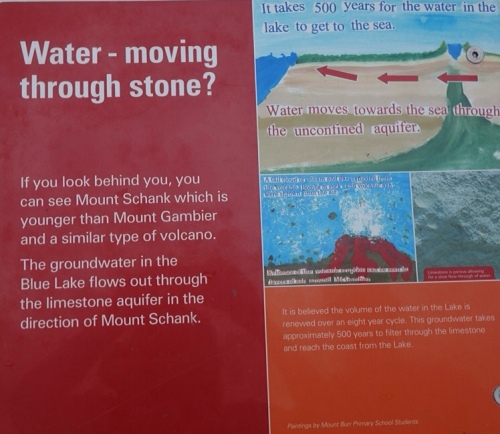

Mt Gambier is one of the youngest volcanos in Australia. Once upon a time, fifteen to forty million years ago, the area was covered in a shallow sea rich in animal life, the remains of which gradually formed limestone. That's the white layer just above the surface of the lake, extending deep down. Long ago, my father-in-law built a house on his opal mine claim out of just such limestone, complete with fossils, backloaded from South Australia by his truckie son.

Four to five thousand years ago, lava flowed over the countryside through fractures in the limestone. The lava cooled and solidified to form a layer of basalt up to 20 metres thick.

The real drama seems to have occurred when groundwater percolated down and became superheated steam when it encountered the hot lava. Pressure built up and large volumes of molten rock blasted through the basalt layer. Bombs of basalt and limestone, weighing up to twenty tonnes were hurled out. Explosive eruptions deposited layers of ash and rocks to form the present crater. The rim walk gave us remarkable cut-away views of the layers of volcanic ash.

The story of the volcano is portrayed by local school-children on panels around the lake.

The Buandig people from near Mount Gambier tell the story of the giant Craitbul and his family who wandered about the area looking for a place to settle and live in peace. They camped and made ovens at Mount Muirhead and Mount Schank but were frightened away from both places by the moaning voice of a bird spirit. They managed to escape from the bird spirit by moving to Mount Gambier where they lived for a long time. Again they made an oven but one day water came up from beneath them and put out their fire. They made other ovens but these were also put out by water coming from beneath them. They made four ovens like this which are now the four craters of Mount Gambier.

Mt Schank

The one thing J really wanted to do on this volcano expedition was take the “adventurous track” down into the crater of Mt Schank. I knew immediately – that word “adventurous” – he'd be making the descent alone. However, I did walk (struggle would be a more appropriate word) up the white steps, stopping at each landing and castigating myself for unfitness as I took in the increasingly expansive view of limestone plains as I rose to 122 metres above sea level.

When I reached the rim, I could see J's tiny figure already almost at the bottom of the crater (later I discovered he'd already walked around the rim and spent ten minutes in an encounter with an echidna.) One side of the crater wall was vegetated, the other a bleak steep rocky wall. I began to walk around the narrow rim, glad of my walking stick on the rough track as land fell away from me on both sides. I enjoyed not trying to keep up, and settled myself on a rock to let my mind roam free and think about our journey so far. I heard footsteps and J appeared feeling triumphant. He'd not only negotiated “the adventurous track”, but clambered up the rocky face instead of retracing his steps.

Both Mount Gambier and Mount Schank have been classified as geological monuments by the Geological Society of Australia. This protects them against major changes from future development.

What a great geological lesson, Meg. I think I wouldn’t have climbed down into the crater, and even would have been nervous at the top, with both sides dropping away. What fun that J encountered an echidna. 🙂

LikeLike

Maybe you visited the lake in a previous life! What an amazing landscape Meg and a wonderful discovery for you both. I’d be back with you going slowly, so as not to miss anything of course 😉 When I went to Etna it had erupted a little while before so I couldn’t walk up to the rim, but my daughter did a few years earlier. How lucky this one is peaceful!

LikeLike

There’s never enough time to go slowly. We’re very conscious of time disappearing. Maybe every trip is a reconnaissance that won’t lead to further exploration. We missed so many delights. Etna, eh? What a lot of adventures you’ve had.

You’re generous to posit previous life rather than defective memory!

LikeLike

Love the explanation of how the four craters came to be. Well done on climbing all those white steps. 🙂

LikeLike

It’s a curse that climbing those steps was such an effort – or rather it’s the outcome of only walking idly along flat surfaces, instead of trotting up hills. I’m always reluctant to begin walking, and always glad that I did!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now we’ve moved to Florida, everything is so flat. I do miss the ups and downs of our place in South Africa, especially the staircase to our first floor.

LikeLike

When I lived in Broken Hill (not dead flat, but flat enough) I used to relish the first hilling as, driving back to the coast, I emerged from the great flat western plains, although the plains were always good for cloudscapes.

LikeLike